Working with Files#

We don’t have better algorithms. We just have more data.

— Peter Norvig

Slides/PDF#

In programs, data must be loaded and saved regularly. This is done on computers using files that are organized into directories. In the previous section on packages, we have already seen some examples that work with files. We now want to explore them in more detail.

Reading Files#

A typical task is loading files. For this, Python provides the open() function with the r (read) flag. For this, you pass to the open() function the path of the file to be loaded and also the mode of the file, i.e., whether the file is a text file t or a binary file b.

The open() function is usually used within the with construct, which assigns the file to a variable (fi) and automatically closes the file after the block ends. To read the contents of the file, we use the read() method of the file object.

with open("geometry/shapes/Line.py", "tr") as fi:

file_contents = fi.read()

print(f"File type {type(fi)}")

print(f"Type of variable {type(file_contents)}\n")

print(file_contents)

File type <class '_io.TextIOWrapper'>

Type of variable <class 'str'>

from geometry.points.ImmutablePoint import ImmutablePoint

class Line:

def __init__(self, start: ImmutablePoint, end: ImmutablePoint):

if not isinstance(start, ImmutablePoint):

raise TypeError("start not of type ImmutablePoint")

if not isinstance(end, ImmutablePoint):

raise TypeError("end not of type ImmutablePoint")

self.start = start

self.end = end

def length(self):

return self.start.distance(self.end)

In the same way, binary files can also be read. For this, we replace the file type t with the binary b and load the file. We can see that the data type of the loaded file contents now changes to byte. If we print the file contents, we also immediately see the special characters in the file such as \r and \n, which denote line breaks.

with open("geometry/shapes/Line.py", "br") as fi:

file_content = fi.read()

print(f"Data type of file {type(fi)}")

print(f"Data type of variable {type(file_content)}\n")

print(file_content)

Data type of file <class '_io.BufferedReader'>

Data type of variable <class 'bytes'>

b'from geometry.points.ImmutablePoint import ImmutablePoint\n\nclass Line:\n def __init__(self, start: ImmutablePoint, end: ImmutablePoint):\n if not isinstance(start, ImmutablePoint):\n raise TypeError("start not of type ImmutablePoint")\n if not isinstance(end, ImmutablePoint):\n raise TypeError("end not of type ImmutablePoint")\n self.start = start\n self.end = end\n\n def length(self):\n return self.start.distance(self.end)'

Writing files#

In the same way, we can also create new files using the open() function. For this, we use the shorthand w (write). Here too, text files are distinguished with t and binary files with b. To write the file, we use the write() method of the file object fo.

with open("meineDatei.txt", "tw") as fo:

fileContent = "Meine eigener Inhalt"

fo.write(fileContent)

To verify, we read the file again.

with open("meineDatei.txt", "tr") as f:

print(f.read())

Meine eigener Inhalt

It’s important to note that the file will be overwritten completely.

with open("meineDatei.txt", "tw") as fo:

date_content = "Neuer Inhalt"

fo.write(date_content)

with open("meineDatei.txt", "tr") as fi:

print(fi.read())

Neuer Inhalt

File existence test#

Often you want to check whether a file already exists and load it accordingly or, for example, recreate it. The standard library os, which we have already learned about, offers such functions and more.

import os

if os.path.exists("meineDatei.txt"):

print("Datei existiert")

else:

print("Datei existiert noch nicht")

Datei existiert

List files#

To list all files in a directory named folder, we can use the os.listdir() function. With the os.path.isfile() function, we can check whether the name refers to a file or a directory. If it is a file, we can open it with the open function to, for example, load its contents and compute the number of lines of code. For this, we use the readlines function instead of the read function to obtain all lines individually in a list.

import os

folder = "geometry/shapes/"

files = 0

codelines = 0

for count, name in enumerate(os.listdir(folder)):

if os.path.isfile(os.path.join(folder, name)):

with open(os.path.join(folder, name), "tr") as fi:

codelines += len(fi.readlines())

files += 1

print(f"{codelines} Codezeilen in {files} Dateien")

64 Codezeilen in 5 Dateien

Delete files#

The os package also provides functions for deleting files. Of course, these should be used with caution.

os.remove("meineDatei.txt")

Common text file formats#

TXT files#

One of the simplest formats for saving text on a computer is text files. They usually have the file extension .txt. We have already used this file extension change above.

JSON files#

Nowadays, structured information is often exchanged in the JSON format. In particular, many APIs of web servers on the Internet use this standard. It has the advantage that the data remains readable by humans and can thus be interpreted by web developers. At its core, the standard resembles the representation of a dict in Python.

For example, we can store the data record for a person in the following dict.

person={

"firstName": "John",

"lastName": "Smith",

"isAlive": True,

"age": 25,

"address": {

"streetAddress": "21 2nd Street",

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"postalCode": "10021-3100"

},

"children": [],

"spouse": None

}

Using the json package, this dataset can now be easily converted into a JSON string and written to a file.

import json

with open("person.json", "tw") as fo:

json.dump(person, fo, indent=2)

Let’s take a look at the file. Since it’s a text file, we can load it with open(name, "tr").

with open("person.json", "tr") as file:

date_content = file.read()

print(date_content)

{

"firstName": "John",

"lastName": "Smith",

"isAlive": true,

"age": 25,

"address": {

"streetAddress": "21 2nd Street",

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"postalCode": "10021-3100"

},

"children": [],

"spouse": null

}

We can see that the JSON representation is very similar to the dictionary person defined above. The only differences are that the capitalized True in Python is written in lowercase here, and the None from Python has been replaced with null. The structure of both representations is, however, identical.

From this text file we can now load our dataset directly back as a dict. For display we will use pretty print this time, because it is easier to read.

from pprint import pprint

with open("person.json", "tr") as fi:

person_loaded = json.load(fi)

print(f"Datentyp {type(person_loaded)}")

pprint(person_loaded)

Datentyp <class 'dict'>

{'address': {'city': 'New York',

'postalCode': '10021-3100',

'state': 'NY',

'streetAddress': '21 2nd Street'},

'age': 25,

'children': [],

'firstName': 'John',

'isAlive': True,

'lastName': 'Smith',

'spouse': None}

The loaded dict corresponds to our original dictionary person. Although the order of the entries has changed, this is not guaranteed in J.

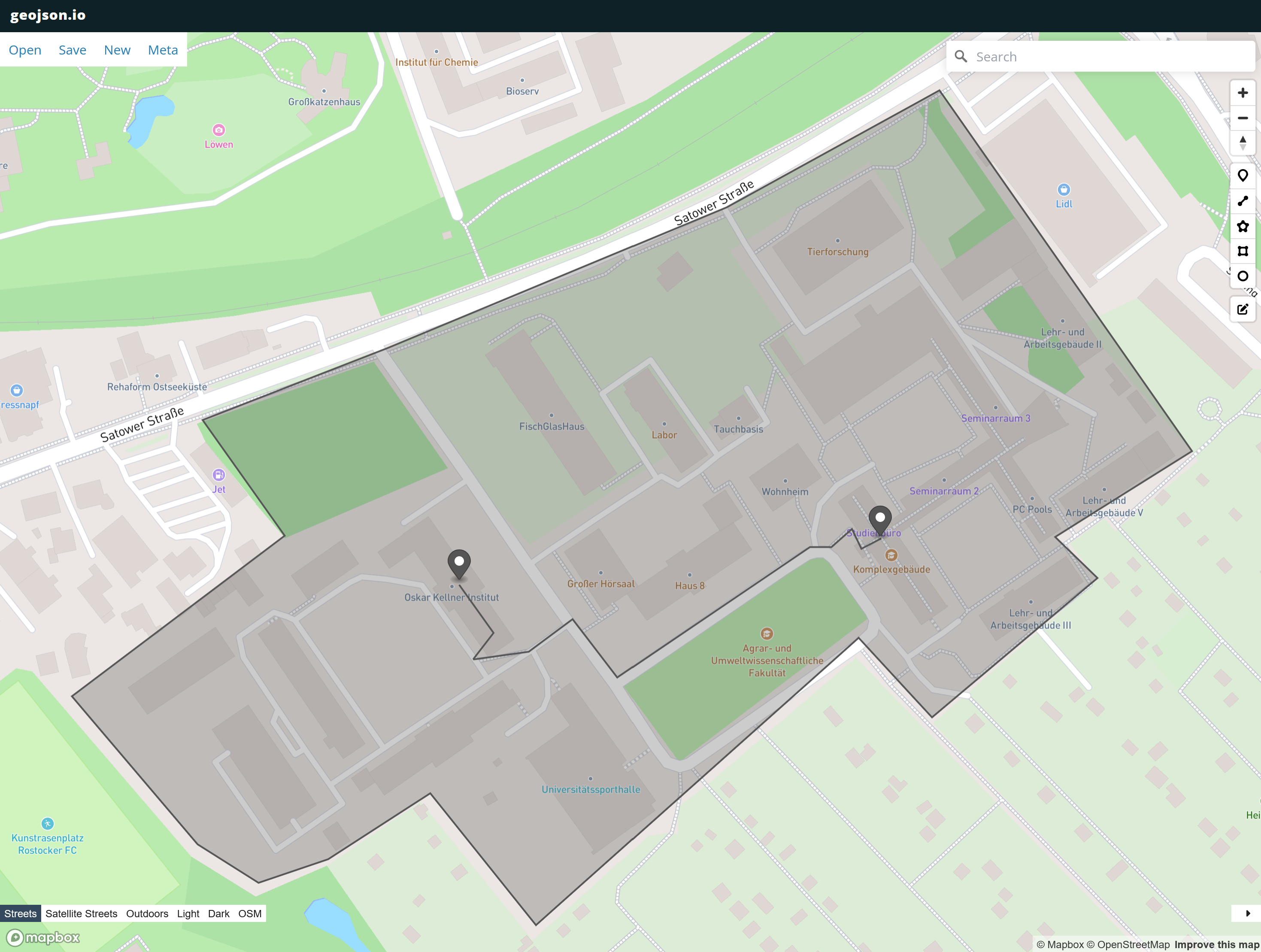

GeoJSON files#

A special variant of the JSON format that is especially relevant for environmental informatics is the standardized GeoJSON format. This JSON-based format defines how certain geometric objects such as points, lines, and polygons should be represented in JSON. Each element is described as a JSON object (dict in Python) and defines the attributes type and coordinates.

A point is defined here as an element of type Point with two coordinates.

point = {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [12.095843457646907, 54.075229197333016]

}

A line is given as a LineString with a list of point coordinates, which are usually the start and end coordinates. If the LineString contains more than two coordinates, we have a polyline.

line_oki_on = {

"type": "LineString",

"coordinates": [

[ 12.095844241344963, 54.075206445655795 ],

[ 12.09606074723871, 54.075028604743636 ],

[ 12.09593084370266, 54.074930156768204 ],

[ 12.096282665780166, 54.07495873846247 ],

[ 12.096558710795335, 54.07507941651065 ],

[ 12.096840168457192, 54.074863466071434 ],

[ 12.098052601464076, 54.07534617726671 ],

[ 12.098187917647891, 54.07534617726671 ],

[ 12.098317821183883, 54.07541286718799 ],

[ 12.098377360305278, 54.075339825840246 ],

[ 12.098501851194726, 54.0753779343855 ]

]

}

A polygon is defined with the type Polygon, whose coordinates are given as a list of one or more closed line strings, such that the end point coincides with the start point.

campus = {

"type": "Polygon",

"coordinates": [

[

[ 12.093402064538196, 54.07479416035679 ],

[ 12.094194380118807, 54.074246433609375 ],

[ 12.094578770845374, 54.074103747303894 ] ,

[ 12.095018074534778, 54.074191200259065 ],

[ 12.095661340649713, 54.074435147002276 ],

[ 12.096328140890677, 54.073947252082434 ],

[ 12.098359920447564, 54.075010487417984 ],

[ 12.098822758261605, 54.07471591412107 ],

[ 12.099866104521425, 54.07523141601854 ],

[ 12.09959938442529, 54.075383303749476 ],

[ 12.100462302384159, 54.075700885391115 ],

[ 12.098869826513692, 54.0770356222489 ],

[ 12.09752838132394, 54.076602988106 ],

[ 12.095394620552042, 54.076082900668524 ],

[ 12.09422575895411, 54.07581595060367 ],

[ 12.094743509729398, 54.07538790639916 ],

[ 12.093402064538196, 54.07479416035679 ]

]

]

}

Since many objects not only have geometry but also additional attributes, there is the helper object Feature, which provides the properties attribute where you can define your own metadata. This way we can define a GeoJSON object to store the position of the OKI.

oki_feature = {

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [12.095843457646907, 54.075229197333016]

},

"properties": {

"name": "OKI",

"addresse": "Justus-von-Liebig-Weg 2",

"stadt": "Rostock",

"postleitzahl": "18059",

"land": "Deutschland"

}

}

auf_feature = {

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [12.098494794410726, 54.075390284810425]

},

"properties": {

"name": "AUF",

"addresse": "Justus-von-Liebig-Weg 6",

"stadt": "Rostock",

"postleitzahl":"18059",

"land": "Deutschland"

}

}

oki_to_auf_route = {

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": line_oki_to_auf,

"properties": {

"name": "Weg OKI zu AUF",

"stadt": "Rostock",

"postleitzahl":"18059",

"land": "Deutschland"

}

}

campus_to_auf = {

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": campus,

"properties": {

"name": "Campus",

"stadt": "Rostock",

"postleitzahl":"18059",

"land": "Deutschland"

}

}

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[17], line 33

1 oki_feature = {

2 "type": "Feature",

3 "geometry": {

(...) 13 }

14 }

16 auf_feature = {

17 "type": "Feature",

18 "geometry": {

(...) 28 }

29 }

31 oki_to_auf_route = {

32 "type": "Feature",

---> 33 "geometry": line_oki_to_auf,

34 "properties": {

35 "name": "Weg OKI zu AUF",

36 "stadt": "Rostock",

37 "postleitzahl":"18059",

38 "land": "Deutschland"

39 }

40 }

42 campus_to_auf = {

43 "type": "Feature",

44 "geometry": campus,

(...) 50 }

51 }

NameError: name 'line_oki_to_auf' is not defined

A collection of Features is stored in a FeatureCollection. It includes, besides the type, the features list.

features = {

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"features": [

oki,

on,

path_oki_on,

campus_on

]

}

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[18], line 4

1 features = {

2 "type": "FeatureCollection",

3 "features": [

----> 4 oki,

5 on,

6 path_oki_on,

7 campus_on

8 ]

9 }

NameError: name 'oki' is not defined

To process these GeoJSON objects in Python, we can use the geojson package. We’ll install it again with pip.

The input is a shell command, not Python code. Please provide the Python source you’d like translated (German to English for variable names, function/class names, docstrings, and inline comments).

Cell In[19], line 1

The input is a shell command, not Python code. Please provide the Python source you’d like translated (German to English for variable names, function/class names, docstrings, and inline comments).

^

SyntaxError: invalid character '’' (U+2019)

The geojson package also provides standard classes for points, lines, and polygons, which we had previously defined ourselves as classes. Due to the broad range of Python packages, you can often find packages that provide corresponding classes for your own problems, so a search is always worthwhile. A point in GeoJSON is created using the package.

from geojson import Point

geojson_point = Point((12.095843457646907, 54.075229197333016))

print(type(geojson_point))

print(geojson_point)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[20], line 1

----> 1 from geojson import Point

3 geojson_point = Point((12.095843457646907, 54.075229197333016))

4 print(type(geojson_point))

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'geojson'

New instances can also be created directly from JSON. For this, we use the package’s loads function. It converts a JSON string into an object. To create the JSON string, we convert the dictionary punkt into a string using the json.dumps() function.

import geojson

import json

json_str = json.dumps(point)

geojson_point = geojson.loads(json_str)

print(type(geojson_point))

print(geojson_point)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[21], line 1

----> 1 import geojson

2 import json

4 json_str = json.dumps(point)

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'geojson'

This is how our entire Feature Collection can be loaded as well.

import geojson

import json

json_str=json.dumps(features)

gson_features=geojson.loads(json_str)

print(type(gson_features))

print(gson_features)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[22], line 1

----> 1 import geojson

2 import json

4 json_str=json.dumps(features)

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'geojson'

The advantage of GeoJSON objects is that there are many other packages available to analyze this format. If we want to visualize our feature collection on a map, we can use the geojsonio package.

# pip install geojsonio --quiet

import geojsonio

geojsonio.display(json_str)

If we follow the link, we reach a webpage that displays the polygons, the line, and the points.

We will learn about additional applications of GeoJSON during the exercise.

XML#

XML is another very widespread file format. All websites on the Internet use, for example, this format. It is older than JSON and still very popular because it allows schemas (XLS) to be defined, against which the file can be validated. This ensures, for example, that HTML files are valid.

With the help of the external packages dicttoxml and xmltodict, XML files can also be written and read easily. We install them with pip.

import subprocess

subprocess.run(["pip", "install", "dicttoxml", "xmltodict", "--quiet"], check=True)

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/mdurl-0.1.2-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/typing_inspection-0.4.1-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/httpx_sse-0.4.1-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/uvicorn-0.34.3-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/annotated_types-0.7.0-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/python_multipart-0.0.20-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/pydantic_core-2.33.2-py3.12-macosx-11.0-arm64.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/the_wall-0.1.0-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/markdown_it_py-3.0.0-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/typer-0.16.0-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/rich-14.0.0-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/shellingham-1.5.4-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/mcp-1.10.1-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/starlette-0.47.1-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/pydantic_settings-2.10.1-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/sse_starlette-2.3.6-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

DEPRECATION: Loading egg at /opt/miniconda3/lib/python3.12/site-packages/pydantic-2.11.7-py3.12.egg is deprecated. pip 24.3 will enforce this behaviour change. A possible replacement is to use pip for package installation. Discussion can be found at https://github.com/pypa/pip/issues/12330

CompletedProcess(args=['pip', 'install', 'dicttoxml', 'xmltodict', '--quiet'], returncode=0)

with open("person.xml", "tr") as fi:

date_content = fi.read()

print(date_content)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[27], line 1

----> 1 with open("person.xml", "tr") as fi:

2 date_content = fi.read()

3 print(date_content)

File ~/Documents/code/Lehre/ProgrammierUebung/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages/IPython/core/interactiveshell.py:343, in _modified_open(file, *args, **kwargs)

336 if file in {0, 1, 2}:

337 raise ValueError(

338 f"IPython won't let you open fd={file} by default "

339 "as it is likely to crash IPython. If you know what you are doing, "

340 "you can use builtins' open."

341 )

--> 343 return io_open(file, *args, **kwargs)

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'person.xml'

import xmltodict

from pprint import pprint

with open("person.xml", "rt") as fi:

person_loaded = xmltodict.parse(fi.read(), xml_attribs=False)

print(f"Datentyp {type(person_loaded)}")

pprint(person_loaded)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[28], line 1

----> 1 import xmltodict

2 from pprint import pprint

4 with open("person.xml", "rt") as fi:

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'xmltodict'

Here too, the loaded dict matches our original.

CSV files#

Tables and measurements are frequently exchanged as CSV files. This is a very simple format in which the first line of the text file contains the column names, and then each line represents a row of the table. All values are separated by commas ,. Since the comma is used as the decimal separator in German, a ; or a tab character \t is often used here.

For processing tables, Python typically uses the pandas library. For example, if we want to store the data set of two people, we first convert it into a pandas DataFrame.

people=[

{"FirstName":"John", "LastName":"Smith", "IsAlive":True, "Age":25},

{"FirstName":"Mary", "LastName":"Sue", "IsAlive":True, "Age":30}

]

import pandas as pd

table = pd.DataFrame(people)

table

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[30], line 1

----> 1 import pandas as pd

3 table = pd.DataFrame(people)

4 table

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'pandas'

We can now save these as a CSV file.

table.to_csv("leute.csv", index=False) # index=False ensures that the row indices 0 and 1 are omitted

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[31], line 1

----> 1 table.to_csv("leute.csv", index=False) # index=False ensures that the row indices 0 and 1 are omitted

NameError: name 'table' is not defined

We’ll read the file back in as a test. Since it’s text-based, we can use open() with tr.

with open("leute.csv", "tr") as fi:

date_content = fi.read()

print(date_content)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[32], line 1

----> 1 with open("leute.csv", "tr") as fi:

2 date_content = fi.read()

3 print(date_content)

File ~/Documents/code/Lehre/ProgrammierUebung/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages/IPython/core/interactiveshell.py:343, in _modified_open(file, *args, **kwargs)

336 if file in {0, 1, 2}:

337 raise ValueError(

338 f"IPython won't let you open fd={file} by default "

339 "as it is likely to crash IPython. If you know what you are doing, "

340 "you can use builtins' open."

341 )

--> 343 return io_open(file, *args, **kwargs)

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'leute.csv'

We can now load the CSV file back into a table.

table_read = pd.read_csv("leute.csv")

table_read

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[33], line 1

----> 1 table_read = pd.read_csv("leute.csv")

2 table_read

NameError: name 'pd' is not defined

And convert it back into the Dictionary.

table_read.to_dict("records")

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[34], line 1

----> 1 table_read.to_dict("records")

NameError: name 'table_read' is not defined

Typical binary file formats#

XLS files#

These CSV files can also be easily opened in other programs such as Microsoft Excel, or saved from there. Excel’s native format is .xlsx files. We can also write these directly from pandas using the openpyxl package. We install openpyxl using pip.

Please provide the Python code containing German variable names, function/class names, docstrings, or inline comments that you would like translated. I will translate only those elements to natural English without altering the program logic.

Cell In[36], line 1

Please provide the Python code containing German variable names, function/class names, docstrings, or inline comments that you would like translated. I will translate only those elements to natural English without altering the program logic.

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

After the installation, we can simply export the table as an Excel file.

table.to_excel("leute.xlsx", index=False) # index=False ensures that the row index is omitted

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[37], line 1

----> 1 table.to_excel("leute.xlsx", index=False) # index=False ensures that the row index is omitted

NameError: name 'table' is not defined

This file is currently a binary file. We can’t read it with open() and tr, so we have to use the binary variant with br.

with open("leute.xlsx", "br") as fi:

file_content = fi.read()

print(file_content)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[38], line 1

----> 1 with open("leute.xlsx", "br") as fi:

2 file_content = fi.read()

3 print(file_content)

File ~/Documents/code/Lehre/ProgrammierUebung/.venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages/IPython/core/interactiveshell.py:343, in _modified_open(file, *args, **kwargs)

336 if file in {0, 1, 2}:

337 raise ValueError(

338 f"IPython won't let you open fd={file} by default "

339 "as it is likely to crash IPython. If you know what you are doing, "

340 "you can use builtins' open."

341 )

--> 343 return io_open(file, *args, **kwargs)

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'leute.xlsx'

What we’re seeing is a lot of unreadable binary data. Behind it, in this case, lies a compressed ZIP file, since the .xlsx file format is actually just a ZIP file that contains several XML files.

ZIP files#

ZIP files are files that contain other files and directories and compress them. This allows multiple files to be consolidated into a single file and to take up less space. Therefore ZIP files are commonly used when sending multiple files.

Also, the .xlsx file from Excel is a disguised ZIP file that contains several XML files in the Open XML format.

This can be shown by renaming the file to a .zip file with os.rename().

os.rename("leute.xlsx", "leute.zip")

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[39], line 1

----> 1 os.rename("leute.xlsx", "leute.zip")

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'leute.xlsx' -> 'leute.zip'

If we want to view the files in the ZIP file, we can open them with the ZipFile object from the standard library’s zipfile module. It works just like open(), but for ZIP files. With the namelist method, we can list all the files in the ZIP file.

import zipfile

with zipfile.ZipFile("leute.zip",'r') as zip_file:

for fname in zip_file.namelist():

print(fname)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[40], line 3

1 import zipfile

----> 3 with zipfile.ZipFile("leute.zip",'r') as zip_file:

4 for fname in zip_file.namelist():

5 print(fname)

File ~/.local/share/uv/python/cpython-3.12.11-macos-aarch64-none/lib/python3.12/zipfile/__init__.py:1336, in ZipFile.__init__(self, file, mode, compression, allowZip64, compresslevel, strict_timestamps, metadata_encoding)

1334 while True:

1335 try:

-> 1336 self.fp = io.open(file, filemode)

1337 except OSError:

1338 if filemode in modeDict:

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'leute.zip'

To read a single file from the ZIP file, we can use the read() method. For example, loading xl/worksheets/sheet1.xml, which contains our data, will show our data in the typical XML structure.

import zipfile

from pprint import pprint

with zipfile.ZipFile("leute.zip",'r') as zip_file:

xml_file = zip_file.read("xl/worksheets/sheet1.xml")

print(xml_file)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[41], line 4

1 import zipfile

2 from pprint import pprint

----> 4 with zipfile.ZipFile("leute.zip",'r') as zip_file:

5 xml_file = zip_file.read("xl/worksheets/sheet1.xml")

6 print(xml_file)

File ~/.local/share/uv/python/cpython-3.12.11-macos-aarch64-none/lib/python3.12/zipfile/__init__.py:1336, in ZipFile.__init__(self, file, mode, compression, allowZip64, compresslevel, strict_timestamps, metadata_encoding)

1334 while True:

1335 try:

-> 1336 self.fp = io.open(file, filemode)

1337 except OSError:

1338 if filemode in modeDict:

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'leute.zip'

Using the parse function of the xmltodict package, for example, we can convert this XML file into a dict in Python.

xml_dict = xmltodict.parse(xml_file, xml_attribs=False)

pprint(xml_dict)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[42], line 1

----> 1 xml_dict = xmltodict.parse(xml_file, xml_attribs=False)

2 pprint(xml_dict)

NameError: name 'xmltodict' is not defined

Our original dictionary leute, which we defined above, is no longer evident in this dictionary. That’s because this format was defined by Microsoft Excel and not specifically designed for our purposes. However, it’s important to note that the format is indeed human-readable, so today many other tools, such as LibreOffice, Google Docs, etc., can read and write this format. This is an important reason for using open XML formats.